If you’ve ever gone to a theatrical production, chances are you paid the most attention to the actors and set. However, there’s much more to a successful stage show than those two factors. There’s costume design, the sound crew and perhaps most overlooked of all, the lighting.

Good lighting is critical for a successful theatrical production. Even the audience members closest to the stage sit at a distance, and for those sitting in the back, it can be even more challenging to see what’s happening on stage. Inadequate lighting makes a scene look flat or obscures the actors, while well-done lighting emphasizes them and helps the audience focus on their performances. Proper lighting can even help set a performance’s tone, changing what might usually be a lighthearted scene into something serious.

There are many different stage lighting techniques, made for various stages, lighting setups and productions. Today, we’ll discuss the McCandless method, a well-known approach for many modern stage productions.

Before we get into the McCandless lighting method, we first need to discuss the man it takes its name from. Stanley McCandless was born in Chicago in May 1897, and graduated from the University of Wisconsin-Madison in 1920. In 1923, he earned an architectural degree from Harvard University. At first, he joined an architectural firm, but eventually, he moved on to the theater department at Yale University, along with his Harvard acquaintance George Pierce Baker.

McCandless was one of the first instructors in Yale’s drama department. His courses focused on theatrical lighting techniques. McCandless was interested in the artistic and technical elements of stage lighting. In addition to teaching, he served as a theatrical consultant, and designed house lights for the Centre Theater in New York’s Radio City that used the precursors for modern ellipsoidal reflector spotlights.

At Yale, McCandless began to publish books detailing his lighting methods. These included Syllabus of Stage Lighting, published in 1927, and A Method of Lighting the Stage, published in 1932. In the latter, he detailed the lighting process that would eventually take his name and become a well-known technique in many modern theaters.

McCandless stayed at Yale until 1964, when he retired professor emeritus, an honorary title for professors who wish to retire while remaining active in the scholarly community. He died at age 70 in 1967. Today, theater experts call him the father or even god of modern lighting design.

Stage lighting is about much more than keeping the stage bright enough for the audience to see. It keeps the stage properly illuminated — not only so the audience can see what’s happening, but so the actors can see each other and the set pieces. It creates a visual tone that sets the scene, whether that’s bright, friendly lighting for an opening song, stark lighting for a dramatic confrontation or warm, intimate lighting for a romantic encounter.

Because stage lighting is so crucial for providing visibility and setting the mood, the crew must use the correct lighting for a show. At best, improper lighting can set the incorrect mood or make the actors look uncanny. At worst, it can make everything murky and hard to see for the actors and audience. Depending on the set’s complexity, obscuring the stage from the actors can even be physically dangerous.

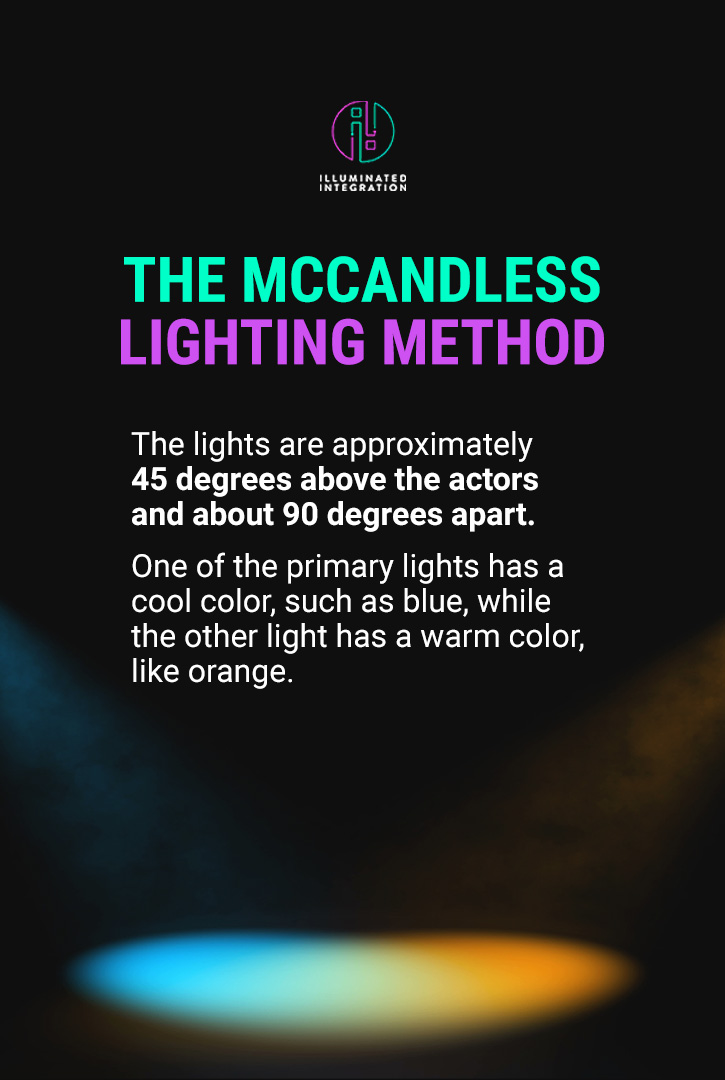

With the McCandless diagonal front lighting method, the lighting crew provides full light with at least two lights coming from opposite sides of the stage. The lights are approximately 45 degrees above the actors and about 90 degrees apart. When combined with smaller fill lights, this creates a “cube” of lighting with the lights at the diagonals.

Angling the lights ensures they cast the correct shadows on the actors’ faces and bodies. Placing lights directly in front of them can make their faces look washed out. The angle helps illuminate their faces while still leaving room for shadows that highlight their features and create depth.

Aside from the positioning and angle, the other essential aspect of the McCandless method is the light color. One of the primary lights has a cool color, such as blue, while the other light has a warm color, like orange. These contrasting colors allow the lights to fill in the shadows created by the other, creating a dramatic sculpting effect on the actor’s face and body.

Like well-done stage makeup, McCandless lighting creates an effect that makes facial features more striking from a distance. It also enhances the shadows on the actors’ clothing. If the general lighting isn’t enough to achieve the desired effect, the crew can use smaller “fill” lights to blend the empty spaces. This lighting method is still prevalent in theaters today for its ability to keep the stage well-lit while simultaneously casting dramatic shadows and sharpening the actors’ features.

As we mentioned, the McCandless technique is one of many stage lighting design methods. However, before you can understand these various approaches, you need to appreciate how stage lights work.

In stage terminology, the lights used in performances are lanterns, and the lightbulbs inside are lamps. Adjusting the lanterns creates different intensities, the term used to describe brightness coming from the lantern. A lower-intensity lantern creates a much weaker, softer light than a higher-intensity one. If the light crew wants a consistent patch of even light across a large space, they use a light called a wash.

Diffusing lights creates a softer effect over a wider area, instead of a single, narrowed beam used as a spotlight. Tools called barn doors and shutters help lighting techs achieve this effect. A barn door is a pair or quartet of metal flaps on a light that provide hard edges, while a shutter is a round fixture, similar to the shutter on a camera, that widens or narrows the light beam.

While lamps can come in different colors, a standard way to change a stage light’s color is to use a gel. Gels are translucent, colored pieces of plastic slotted on the front of the lantern. These tools allow a single light to produce many different colors instead of forcing the crew to refit a new lamp every time they want a color change.

There are four lighting positions in theater.

Lighting technicians fill these light positions with various light types, including ellipsoidal, followspots, Fresnels and strip lights. Each has a different function — for example, an ellipsoidal light creates an intense, well-defined beam of light that’s excellent for front lighting, while Fresnels create concentric layers of light with varying intensities that make them ideal for washes.

The McCandless lighting method relies on two primary front lights, with backlights, downlights and sidelights used at the lighting crew’s discretion to even out the effect. This technique offers a much more dramatic effect than a general stage light wash, and more variety and depth than a single spotlight focused on someone’s face. While single spotlights add focus, they can also make an actor’s face appear flat and washed out due to a lack of shadows.

The McCandless approach also uses a blend of warm and cool colors to create depth of shadow, instead of a single color that’s either warm, cool or neutral. Again, this adds more depth and variety than a single color.

In essence, the McCandless method differs from other lighting styles in its dramatic, artistic sculpting effect that still provides sufficient illumination to the scene.

As you can see, the McCandless method is ideal for anyone who wishes to achieve a dramatic, sculpted effect on their actors. However, we’ve only discussed the technique as it applies to a proscenium stage, which is likely familiar to you if you’ve seen a play. The stage faces the audience and sinks back into the wall. It usually has a pit in the front for the orchestra and an arch above it.

However, the proscenium stage is only one kind of theater stage. There are many stage types, with different shapes and audience angles. For example, a thrust stage extends into the audience, creating many different potential angles to view the actors. If you’ve ever seen a fashion show, you’re probably familiar with thrust stages.

Thrust stages can create intimacy between the performers and the audience — however, they also cause a logistics problem when using the McCandless method. This technique depends on using two opposing lights to cast dramatic shadows on the actors, with select smaller lights smoothing out the effect where necessary. With a thrust stage, the audience members view the actors from drastically different angles, making it impossible to achieve a consistent lighting effect from all sides.

While a thrust stage doesn’t allow for universal lighting, it’s still possible to create a general McCandless effect and provide your actors with decent lighting. Setting up the McCandless method for a thrust stage involves several steps.

With this method, you should achieve a largely consistent McCandless lighting effect from many different angles.

Stage lighting is an essential facet of theatrical production — not only to help the audience and actors see, but also to create the appropriate depth and tone for the scene. With the McCandless method, the light crew uses two opposing lights to create dramatic shadows that sculpt the actors’ faces. To do this, theaters need an effective lighting system — ideally, one that’s also part of a unified audio and video system.

If you’re looking for an efficient, modern AVL system, consider Illuminated Integration. We provide a seamless, well-integrated experience, regardless of your project’s size or complexity. Our customized designs are entirely original, meaning you’ll be getting what you need instead of a standard cookie-cutter system experience. Contact us, tell us about your project and connect with our trained team today!